Advocate's Guide to the Florida Medicaid PROGRAM

July 2022 (2ND Edition)

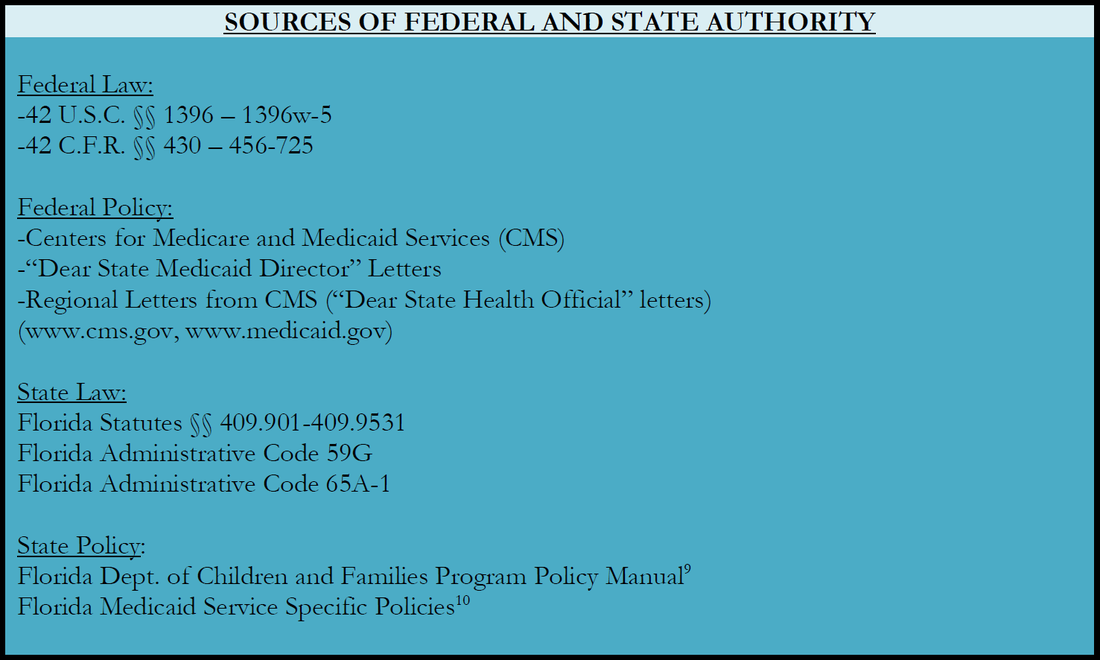

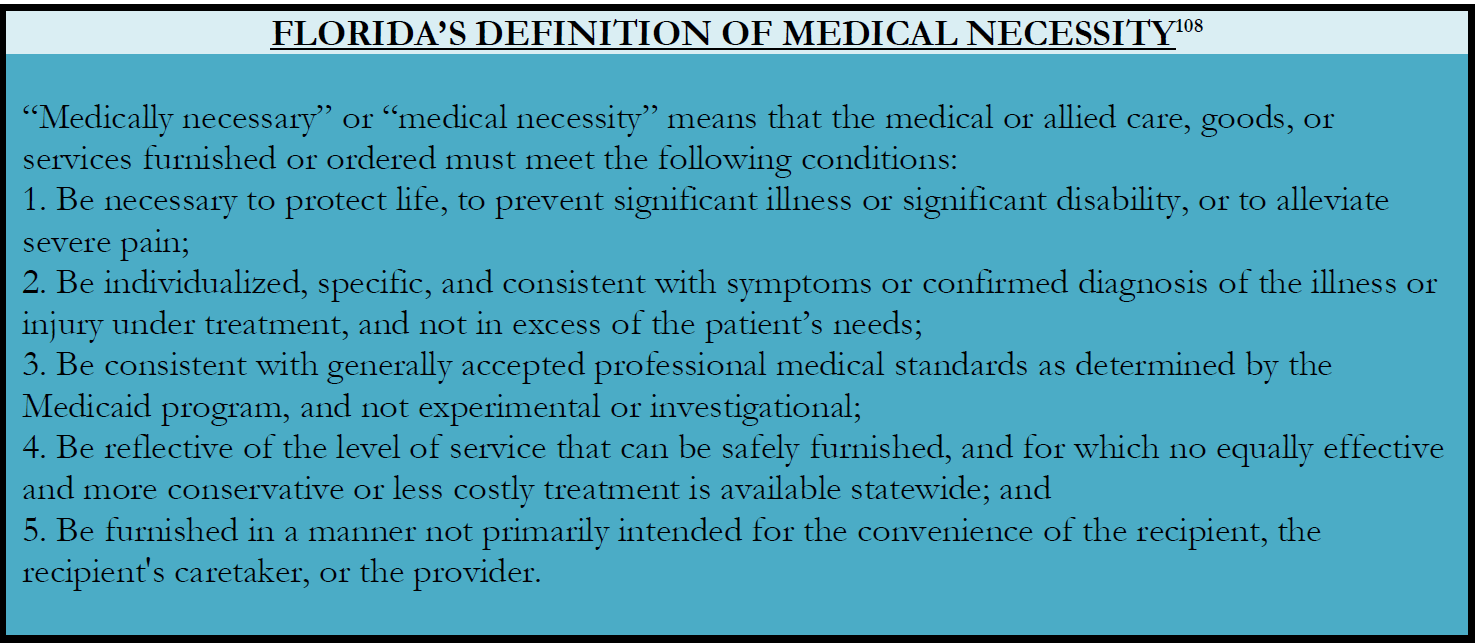

The Advocate’s Guide to the Florida Medicaid Program provides a useful roadmap to a complex and critical safety net program currently serving over 5 million Floridians.

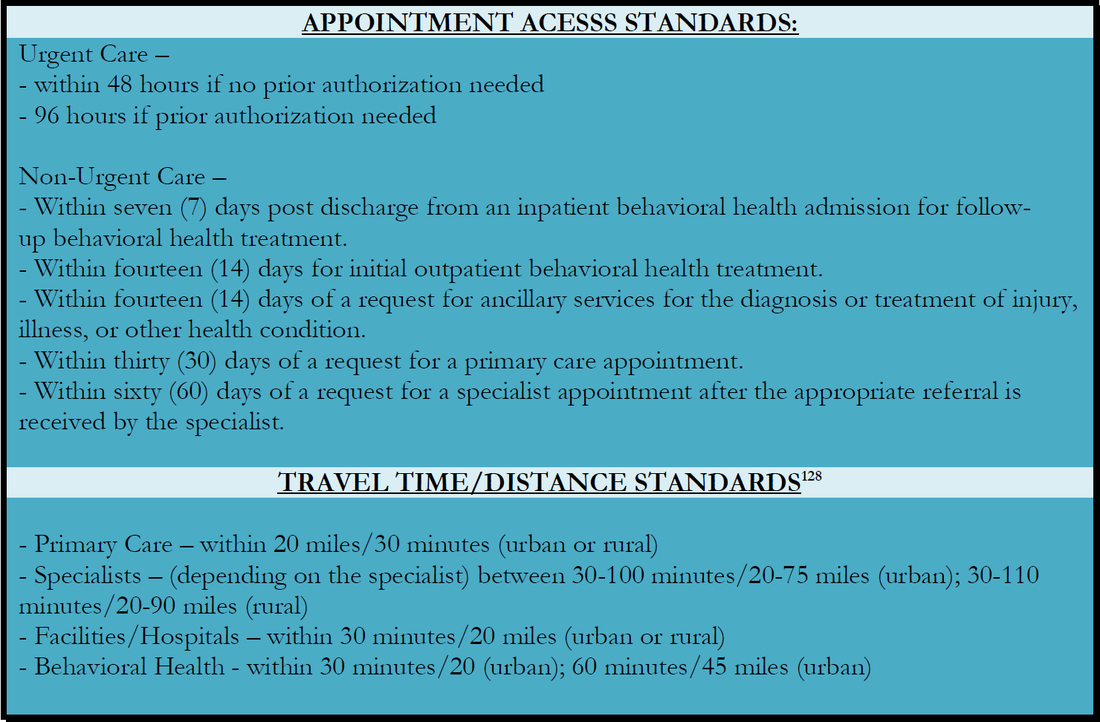

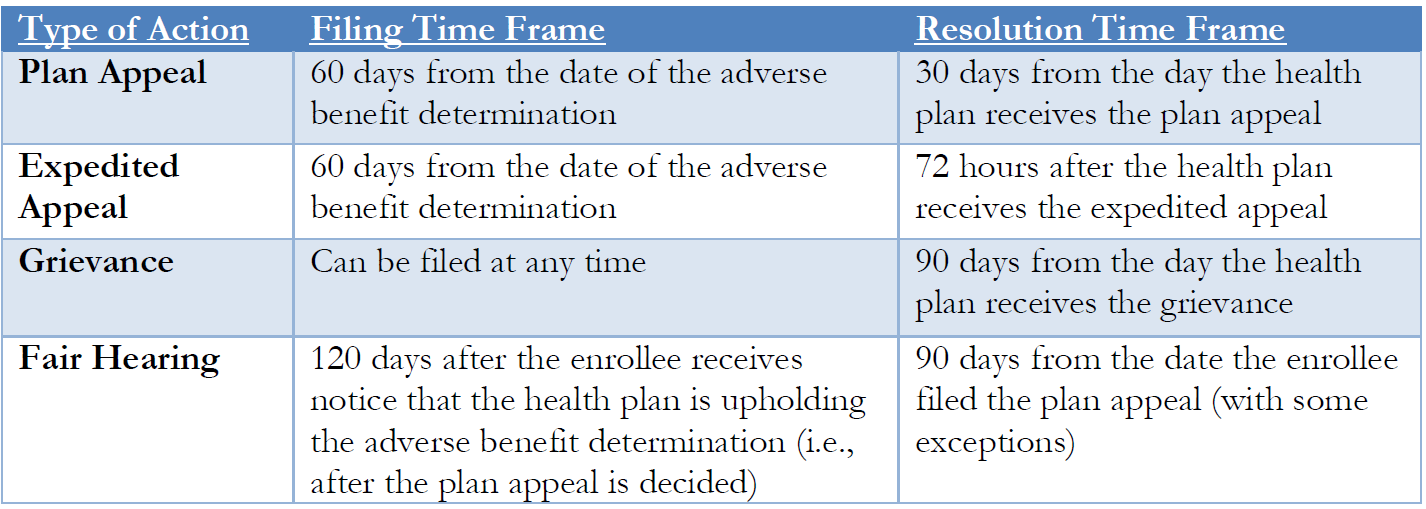

The Guide looks at who is eligible for Medicaid; how to apply; what to do if an application is denied or delayed; what to do if eligibility is terminated; what services are covered; how managed care works; and what to do if a beneficiary’s services are denied, delayed, terminated or reduced.

The Guide looks at who is eligible for Medicaid; how to apply; what to do if an application is denied or delayed; what to do if eligibility is terminated; what services are covered; how managed care works; and what to do if a beneficiary’s services are denied, delayed, terminated or reduced.